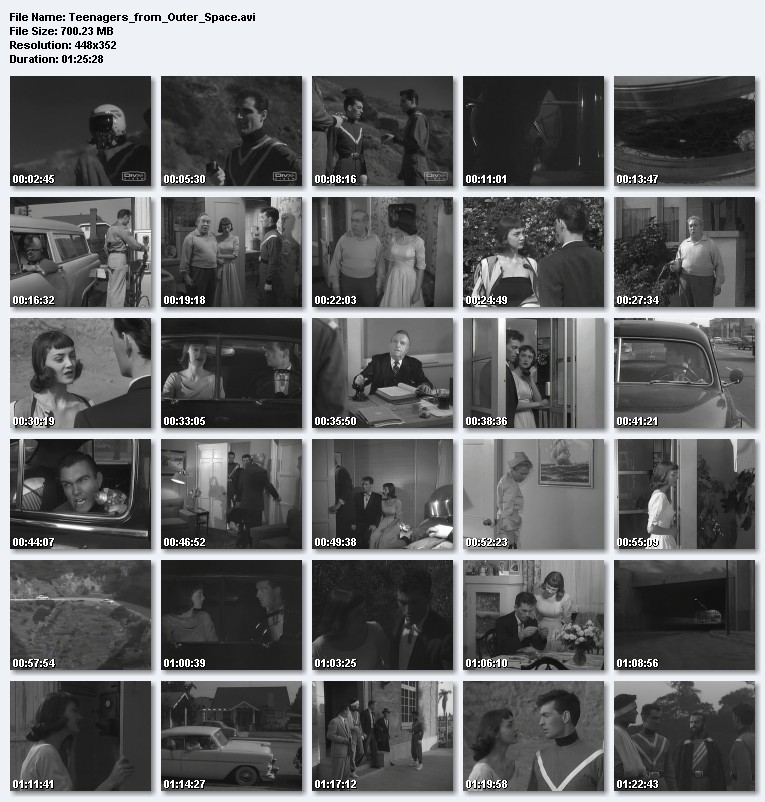

Jun 21, 1999 - Torrent details. Download, MST3K - 0315 - 20020131 - Teenage Caveman.avi. EDonkey Link: ed2k://|file|MST3K+-+0315+-+20020131+-+Teenage+. OF THE COLOSSAL BEAST; 404-TEENAGERS FROM OUTER SPACE. 1958-The Brain Eaters (directed by Bruno VeSota); and 1959-T-Bird Gang.

Douglas Adams: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979)

Originating as a BBC radio series in 1978, Douglas Adams's inspired melding of hippy-trail guidebook and sci-fi comedy turned its novelisations into a publishing phenomenon. Douglas wrote five parts from 1979 onwards (the first sold 250,000 in three months), introducing the world to Marvin the Paranoid Android, the computer Deep Thought, space guitarist Hotblack Desiato (named after Adams's local estate agent) and the Guide itself, a remarkably prescient forerunner to the internet.

Andrew Pulver

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Brian W Aldiss: Non-Stop (1958)

Aldiss's first novel is a tour-de-force of adventure, wonder and conceptual breakthrough. Set aboard a vast generation starship millennia after blast-off, the novel follows Roy Complain on a voyage of discovery from ignorance of his surroundings to some understanding of his small place in the universe. Complain is spiteful and small-minded but grows in humanity as his trek through the ship brings him into contact with giant humans, mutated rats and, ultimately, a wondrous view of space beyond the ship.

Eric Brown

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Isaac Asimov: Foundation (1951)

One of the first attempts to write a comprehensive 'future history', the trilogy - which also includes Foundation and Empire (1952) and Second Foundation (1953) - is Asimov's version of Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, set on a galactic scale. Hari Seldon invents the science of psychohistory with which to combat the fall into barbarianism of the Human Empire, and sets up the Foundation to foster art, science and technology. Wish-fulfilment of the highest order, the novels are a landmark in the history of science fiction.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Margaret Atwood: The Blind Assassin (2000)

On planet Zycron, tyrannical Snilfards subjugate poor Ygnirods, providing intercoital entertainment for a radical socialist and his lover. We assume she is Laura Chase, daughter of an Ontario industrialist, who records their sex and sci-fi stories in a novel, The Blind Assassin. Published posthumously by Laura's sister, Iris, the book outrages postwar sensibilities. Iris is 83 in the cantankerous present-day narrative, and ready to set the story straight about the suspicious deaths of her sister, husband and daughter. In this Booker prize-winning novel about novels, Atwood bends genre and traps time, toying brilliantly with the roles of writing and reading.

Natalie Cate

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Paul Auster: In the Country of Last Things (1987)

Anna Blume, 19, arrives in a city to look for her brother. She finds a ruin, where buildings collapse on scavenging citizens. All production has stopped. Nobody can leave, except as a corpse collected for fuel. Suicide clubs flourish. Anna buys a trolley and wanders the city, salvaging objects and information. She records horrific scenes, but also a deep capacity for love. This small hope flickers in a world where no apocalyptic event is specified. Instead, Auster creates his dystopia by magnifying familiar flaws and recycling historical detail: the novel's working title was 'Anna Blume Walks Through the 20th Century'.

NC

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Iain Banks: The Wasp Factory (1984)

A modern-gothic tale of mutilation, murder and medical experimentation, Banks's first novel - described by the Irish Times as 'a work of unparalleled depravity'- is set on a Scottish island inhabited by the ultimate dysfunctional family: a mad scientist and his unbalanced sons, older brother Eric, who has been locked up for everyone's safety, and Frank, the 16-year-old narrator, tormented by a freak accident that cost him his genitals. Frank's victims are mostly animals - but he has found time to kill a few children …

Phil Daoust

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Iain M Banks: Consider Phlebas (1987)

Space opera is unfashionable, but Banks couldn't care less. 'You get the opportunity to work on a proper canvas,' he says. 'Big, big brushes, broad strokes.' The strokes have rarely been broader than in Banks's Culture novels, about a galaxy-spanning society in which humans and artificial intelligences are united by a love of parties, adventure and a damn good fight. Consider Phlebas introduced the first of many misguided or untrustworthy heroes - Horza, who can change his body just by thinking about it - and a typically Banksian collision involving two giant trains in an subterranean station.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Clive Barker: Weaveworld (1987)

Life's rich tapestry is just that in Clive Barker's fantasy. A magic carpet is the last refuge of a people known as the Seerkind, who for centuries have been hunted by both humans and the Scourge, a mysterious being that seems determined to live up to its name. When it all starts to unravel, the carpet people's best hope is a pigeon-fancying insurance clerk and his half-Seerkind companion. Yes, it sounds twee, but as Barker himself said, 'the Seerkind fornicate, fart - they're very far from pure'.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Nicola Barker: Darkmans (2007)

Nicola Barker has been accused of obscurity, but this Booker-shortlisted comic epic has a new lightness of touch and an almost soapy compulsiveness. Set in Ashford, Kent, the kind of everytown that has turned its back on history, the novel dips into the lives of a loosely connected cast of everyday eccentrics who find that history - in the persona of Edward IV's jester - is fighting back. A jumble of voices and typefaces, mortal fear and sarky laughter, the novel is as true as it is truly odd, and beautifully written to boot.

Justine Jordan

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Stephen Baxter: The Time Ships (1995)

In his visionary sequel to Wells's The Time Machine, Baxter continues the adventures of the Time-Traveller. He sends him back to the far future in an attempt to save the Eloi woman Weena, only to find himself in a future timeline diverging from the one he left. Baxter's extraordinary continuation and expansion tackles the usual concerns of the time-travel story - paradox and causality - and goes on to explore many of the themes that taxed Wells: destiny, morality and the perfectibility of the human race.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Greg Bear: Darwin's Radio (1999)

Bear combines intelligence, humour and the wonder of scientific discovery in a techno-thriller about a threat to the future of humanity. A retro-viral plague sweeps the world, infecting women via their sexual partners and aborting their embryos. But the plague is more than it seems ... What might in other hands have been a mere end-of-the-world runaround is transformed by Bear's scientific knowledge into something marvellous, as reason overcomes paranoia and fear.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Alfred Bester: The Stars My Destination (1956)

'Gully Foyle is my name / And Terra is my nation. / Deep space is my dwelling place / And death's my destination …' Marooned in space after an attack on his ship, then ignored by a passing luxury liner, an illiterate mechanic plots revenge on those who left him to die. Somehow surviving, he swiftly gets down to it. Bester's novel updates The Count of Monte Cristo with telepathy, nuclear weapons and interplanetary travel. Those who stumble across it are inevitably surprised to find it was written half a century ago.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Poppy Z Brite: Lost Souls (1992)

Brite's first novel, a lush, decadent and refreshingly provocative take on vampirism told in rich, stylish prose, put her at the forefront of the 1990s horror scene. It's the story of Nothing, an angst-filled teenager who runs away from his adoptive parents to seek out his favourite band. Along the way he joins up with a group of vampires, finds his true family and discovers what he really values, amid much blood, sex, drugs and drink.

Keith Brooke

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Algis Budrys: Rogue Moon (1960)

Al Barker is a thrillseeking adventurer recruited to investigate an alien labyrinth on the moon. Everyone who enters the maze dies, so Barker's doppelganger is transmitted there while he remains in telepathic contact. Barker is the first person to survive the trauma of witnessing their own death, returning again and again to explore. Rogue Moon works as both thriller and character study, a classic novel mapping out a new and sophisticated SF, just as Barker maps the alien maze.

KB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Mikhail Bulgakov: The Master and Margarita (1966)

When the Devil comes to 1930s Moscow, his victims are pillars of the Soviet establishment: a famous editor has his head cut off; another bureaucrat is made invisible. This is just a curtain-raiser for the main event, however: a magnificent ball for the damned and the diabolical. For his hostess, his satanic majesty chooses Margarita, a courageous young Russian whose lover is in a psychiatric hospital, traumatised by the banning of his novel. No prizes for guessing whom Bulgakov identified with; although Stalin admired his early work, by the 1930s he was personally banning it. This magisterial satire was not published until more than 20 years after the writer's death.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Edward Bulwer-Lytton: The Coming Race (1871)

In this pioneering work of British science fiction, the hero is a bumptious American mining engineer who stumbles on a subterranean civilisation. The 'Vril-ya' enjoy a utopian social organisation based on 'vril', a source of infinitely renewable electrical power (commerce promptly produced the beef essence drink, Bovril). Also present are ray guns, aerial travel and ESP. Ironically, the hero finds utopia too boring. He is rescued from death by the Princess Zee, who flies him to safety. The novel ends with the ominous prophecy that the superior race will invade the upper earth - 'the Darwinian proposition', as Bulwer-Lytton called it.

John Sutherland

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Anthony Burgess: A Clockwork Orange (1960)

One of a flurry of novels written by Burgess when he was under the mistaken belief that he had only a short time to live. Set in a dystopian socialist welfare state of the future, the novel fantasises a world without religion. Alex is a 'droog' - a juvenile delinquent who lives for sex, violence and subcult high fashion. The narrative takes the form of a memoir, in Alex's distinctive gang-slang. The state 'programmes' Alex into virtue; later deprogrammed, he discovers what good and evil really are. The novel, internationally popularised by Stanley Kubrick's 1970 film into what Burgess called 'Clockwork Marmalade', is Burgess's tribute to his cradle Catholicism and, as a writer, to James Joyce.

JS

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Anthony Burgess: The End of the World News (1982)

In one of the first split-screen narratives, Burgess juxtaposes three key 20th-century themes: communism, psychoanalysis and the millennial fear of Armageddon. Trotsky's 1917 visit to New York is presented as a Broadway musical; a mournful Freud looks back on his life as he prepares to flee the Nazis; and in the year 2000, as a rogue asteroid barrels towards the Earth, humanity argues over who will survive and what kind of society they will take to the stars.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Edgar Rice Burroughs: A Princess of Mars (1912)

John Carter, a Confederate veteran turned gold prospector, is hiding from Indians in an Arizona cave when he is mysteriously transported to Mars, known to the locals as Barsoom. There, surrounded by four-armed, green-skinned warriors, ferocious white apes, eight-legged horse-substitutes, 10-legged 'dogs', and so on, he falls in love with Princess Dejah Thoris, who might almost be human if she didn't lay eggs. She is, naturally, both beautiful and extremely scantily clad ... Burroughs's first novel, published in serial form, is the purest pulp, and its lack of pretension is its greatest charm.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

William Burroughs: Naked Lunch (1959)

Disjointed, hallucinatory cut-ups form a collage of, as Burroughs explained of the title, 'a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork'. A junkie's picaresque adventures in both the real world and the fantastical 'Interzone', this is satire using the most savage of distorting mirrors: society as an obscene phantasmagoria of addiction, violence, sex and death. Only Cronenberg could have filmed it (in 1991), and even he recreated Burroughs's biography rather than his interior world.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Octavia Butler: Kindred (1979)

Butler's fourth novel throws African American Dana Franklin back in time to the early 1800s, where she is pitched into the reality of slavery and the individual struggle to survive its horrors. Butler single-handedly brought to the SF genre the concerns of gender politics, racial conflict and slavery. Several of her novels are groundbreaking, but none is more compelling or shocking than Kindred. A brilliant work on many levels, it ingeniously uses the device of time travel to explore the iniquity of slavery through Dana's modern sensibilities.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Samuel Butler: Erewhon (1872)

The wittiest of Victorian dystopias by the period's arch anti-Victorian. The hero Higgs finds himself in New Zealand (as, for a while, did the chronic misfit Butler). Assisted by a native, Chowbok, he makes a perilous journey across a mountain range to Erewhon (say it backwards), an upside-down world in which crime is 'cured' and illness 'punished', where universities are institutions of 'Unreason' and technology is banned. The state religion is worship of the goddess Ydgrun (ie 'Mrs Grundy' - bourgeois morality). Does it sound familiar? Higgs escapes by balloon, with the sweetheart he has found there.

JS

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Italo Calvino: The Baron in the Trees (1957)

It is 1767: a boy quarrels with his aristocratic parents and climbs a tree, swearing not to touch the earth again. He ends up keeping his promise, witnessing the French revolution and its Napoleonic aftermath from the perspective of the Italian treetops. Drafted soon after Calvino's break with communism over the invasion of Hungary, the novel can be read as a fable about intellectual commitments. At the same time, it's a perfectly turned fantasy, densely imagined but lightly written in a style modelled on Voltaire and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Chris Tayler

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Ramsey Campbell: The Influence (1988)

Campbell has long been one of the masters of psychological horror, proving again and again that what's in our heads is far scarier than any monster lurking in the shadows. In this novel, the domineering old spinster Queenie dies - a relief to those around her. Her niece Alison inherits the house, but soon starts to suspect that the old woman is taking over her eight-year-old daughter Rowan. A paranoid, disturbing masterpiece.

KB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

The intellectuals' favourite children's story began as an improvised tale told by an Oxford mathematics don to a colleague's daughters; later readers have found absurdism, political satire and linguistic philosophy in a work that, 140 years on, remains fertile and fresh, crisp yet mysterious, and endlessly open to intepretation. Alice, while reading in a meadow, sees a white rabbit rush by, feverishly consulting a watch. She follows him down a hole (Freudian analysis, as elsewhere in the story, is all too easy), where she grows and shrinks in size and encounters creatures mythological, extinct and invented. Morbid jokes and gleeful subversion abound.

JS

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Lewis Carroll: Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871)

The trippier sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and, like its predecessor, illustrated by John Tenniel. More donnish in tone, this fantasy follows Alice into a mirror world in which everything is reversed. Her journey is based on chess moves, during the course of which she meets such figures as Humpty Dumpty and the riddling twins Tweedledum and Tweedledee. More challenging intellectually than the first instalment, it explores loneliness, language and the logic of dreams.

JS

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Angela Carter: Nights at the Circus (1984)

The year is 1899 - and other times. Fevvers, aerialiste, circus performer and a virgin, claims she was not born, but hatched out of an egg. She has two large and wonderful wings. In fact, she is large and wonderful in every way, from her false eyelashes to her ebullient and astonishing adventures. The journalist Jack Walser comes to interview her and stays to love and wonder, as will every reader of this entirely original extravaganza, which deftly and wittily questions every assumption we make about the lives of men and women on this planet.

Carmen Callil

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Michael Chabon: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000)

The golden age of the American comic book coincided with the outbreak of the second world war and was spearheaded by first- and second-generation Jewish immigrants who installed square-jawed supermen as bulwarks against the forces of evil. Chabon's Pulitzer prize-winning picaresque charts the rise of two young cartoonists, Klayman and Kavalier. It celebrates the transformative power of pop culture, and reveals the harsh truths behind the hyperreal fantasies.

XB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Arthur C Clarke: Childhood's End (1953)

Clarke's third novel fuses science and mysticism in an optimistic treatise describing the transcendence of humankind from petty, warring beings to the guardians of utopia, and beyond. One of the first major works to present alien arrival as beneficent, it describes the slow process of social transformation when the Overlords come to Earth and guide us to the light. Humanity ultimately transcends the physical and joins a cosmic overmind, so ushering in the childhood's end of the title

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

GK Chesterton: The Man Who Was Thursday (1908)

Chesterton's 'nightmare', as he subtitled it, combines Edwardian delicacy with wonderfully melodramatic tub-thumping - beautiful sunsets and Armageddon - to create an Earth as strange as any far-distant planet. Secret policemen infiltrate an anarchist cabal bent on destruction, whose members are known only by the days of the week; but behind each one's disguise, they discover only another policeman. At the centre of all is the terrifying Sunday, a superhuman force of mischief and pandemonium. Chesterton's distorting mirror combines spinetingling terror with round farce to give a fascinating perspective on Edwardian fears of (and flirtations with) anarchism, nihilism and a world without god.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Susanna Clarke: Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (2004)

Clarke's first novel is a vast, hugely satisfying alternative history, a decade in the writing, about the revival of magic - which had fallen into dusty, theoretical scholarship - in the early 19th century. Two rival magicians flex their new powers, pursuing military glory and power at court, striking a dangerous alliance with the Faerie King, and falling into passionate enmity over the use and meaning of the supernatural. The book is studded with footnotes both scholarly and comical, layered with literary pastiche, and invents a whole new strain of folklore: it's dark, charming and very, very English.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Michael G Coney: Hello Summer, Goodbye (1975)

This classic by an unjustly neglected writer tells the story of Drove and Pallahaxi-Browneyes on a far-flung alien world which undergoes long periods of summer and gruelling winters lasting some 40 years. It's both a love story and a war story, and a deeply felt essay, ahead of its time, about how all living things are mutually dependant. This is just the kind of jargon-free, humane, character-driven novel to convert sceptical readers to science fiction.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Douglas Coupland: Girlfriend in a Coma (1998)

Coupland began Girlfriend in a Coma in 'probably the darkest period of my life', and it shows. Listening to the Smiths - whose single gave the book its title - can't have helped. This is a story about the end of the world, and the general falling-off that precedes it, as 17-year-old Karen loses first her virginity, then consciousness. When she reawakens more than a decade later, the young people she knew and loved have died, become junkies or or simply lost that new-teenager smell. Wondering what the future holds? It's wrinkles, disillusionment and the big sleep.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Mark Danielewski: House of Leaves (2000)

It's not often you get to read a book vertically as well as horizontally, but there is much that is uncommon about House of Leaves. It's ostensibly a horror story, but the multiple narrations and typographical tricks - including one chapter that cuts down through the middle of the book - make it as much a comment on metatextuality as a novel. That said, the creepiness stays with you, especially the house that keeps stealthily remodelling itself: surely that long, dark, endless corridor wasn't there yesterday ...

Carrie O'Grady

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Marie Darrieussecq: Pig Tales (1996)

It wasn't a problem at first: to be more voluptuous, to have a firmer, more rounded bottom and breasts, to be pinker and more healthy-looking is far from a disadvantage to a girl working in a massage parlour in a sex-crazed dystopian society. But the changes don't stop there: her hunger dominates (her preferred foods are now flowers and raw potatoes), her pleasant plumpness becomes rolls of fat, her glow turns ruddy. A curly tail, trotters and a snout are not far off. Darrieussecq's modern philosophical tale is witty, telling and hearteningly feminist.

Joanna Biggs

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Samuel R Delaney: The Einstein Intersection (1967)

The setting is a post-apocalyptic future, long past the age of humans. Aliens have taken on the forms of human archetypes, in an attempt to come to some understanding of human civilisation and play out the myths of the planet's far past. The novel follows Lobey, who as Orpheus embarks on a quest to bring his lover back from the dead. With lush, poetic imagery and the innovative use of mythic archetypes, Delaney brilliantly delineates the human condition.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Philip K Dick: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968)

Dick's novel became the basis for the film Blade Runner, which prompted a resurgence of interest in the man and his works, but similarities film and novel are slight. Here California is under-populated and most animals are extinct; citizens keep electric pets instead. In order to afford a real sheep and so affirm his empathy as a human being, Deckard hunts rogue androids, who lack empathy. As ever with Dick, pathos abounds and with it the inquiry into what is human and what is fake.

EB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Philip K Dick: The Man in the High Castle (1962)

Much imitated 'alternative universe' novel by the wayward genius of the genre. The Axis has won the second world war. Imperial Japan occupies the west coast of America; more tyrannically, Nazi Germany (under Martin Bormann, Hitler having died of syphilis) takes over the east coast. The Californian lifestyle adapts well to its oriental master. Germany, although on the brink of space travel and the possessor of vast tracts of Russia, is teetering on collapse. The novel is multi-plotted, its random progression determined, Dick tells us, by consultation with the Chinese I Ching.

JS

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Umberto Eco: Foucault's Pendulum (1988)

Foucault's Pendulum followed the massive success of Eco's The Name of the Rose, and in complexity, intrigue, labyrinthine plotting and historical scope it is every bit as extravagant. Eco's tale of three Milanese publishers, who feed occult and mystic knowledge into a computer to see what invented connections are created, tapped into the worldwide love of conspiracy theories, particularly those steeped in historical confusion. As 'The Plan' takes over their lives and becomes reality, the novel turns into a brilliant historical thriller of its own that inspired a similar level of obsession among fans.

Nicola Barr

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Michel Faber: Under the Skin (2000)

A woman drives around the Scottish highlands, all cleavage and lipstick, picking up well-built male hitchhikers - but there's something odd behind her thick pebble glasses ... Faber's first novel refreshes the elements of horror and SF in luminous, unearthly prose, building with masterly control into a page-turning existential thriller that can also be read as an allegory of animal rights. And in the character of Isserley - her curiosity, resignation, wonderment and pain - he paints an immensely affecting portrait of how it feels to be irreparably damaged and immeasurably far from home.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

John Fowles: The Magus (1966)

Determined to extricate himself from an increasingly serious relationship, graduate Nicholas Urfe takes a job as an English teacher on a small Greek island. Walking alone one day, he runs into a wealthy eccentric, Maurice Conchis, who draws him into a succession of elaborate psychological games that involve two beautiful young sisters in reenactments of Greek myths and the Nazi occupation. Appearing after The Collector, this was actually the first novel that Fowles wrote, and although it quickly became required reading for a generation, he continued to rework it for a decade after publication.

David Newnham

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Neil Gaiman: American Gods (2001)

'Nourishing to the soul' was Michael Chabon's verdict on Gaiman's novel, in which ex-con Shadow gets a job driving for a conman who turns out to be a Norse god. Before long, he is embroiled in a battle between ancient and modern deities: Odin, Anansi, Anubis and the Norns on one side, TV, the movies and technology on the other. A road trip through America's sacred places is spiced up by some troublesome encounters with Shadow's unfaithful wife, Laura. She's dead, which always makes for awkward silences.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Alan Garner: Red Shift (1973)

The author of such outstanding mythical fantasies as Elidor and The Owl Service, Garner has been called 'too good for grown-ups'; but the preoccupations of this young adult novel (love and violence, madness and possession, the pain of relationships outgrown and the awkwardness of the outsider) are not only adolescent. The three

narrative strands - young lovers in the 1970s, the chaos of thebetweenalcoholics, English civil war and soldiers going native in a Vietnam-tinged Roman Britain - circle around Mow Cop in Cheshire and an ancient axehead found there. Dipping in and out of time, in blunt, raw dialogue, Garner creates a moving and singular novel.

JJ

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

William Gibson: Neuromancer (1984)

'The sky above the port was the colour of television, tuned to a dead channel.' From the first line of Gibson's first novel, it was clear that a major talent had arrived. This classic of cyberpunk won Nebula, Hugo and Philip K Dick awards, and popularised the term 'cyberspace', which the author described as 'a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions'. A fast-paced thriller starring a washed-up hacker, a cybernetically enhanced mercenary and an almost omnipotent artificial intelligence, it inspired and informed a slew of films and novels, not least the Matrix trilogy.

PD

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Herland (1915)

When three explorers learn of a country inhabited only by females, Terry, the lady's man, looks forward to Glorious Girls, Van, the scientist, expects them to be uncivilised, and Jeff, the Southern gallant, hopes for clinging vines in need of rescue. The process by which their assumptions are overturned and their own beliefs challenged is told with humour and a light touch in Gilman's brilliantly realised vision of a female Utopia where Mother Love is raised to its highest power. Many of Herland's insights are as relevant today as when it was first published a hundred years ago.

Joanna Hines

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

William Golding: Lord of the Flies (1954)

The shadow of the second world war looms over Golding's debut, the classic tale of a group of English schoolboys struggling to recreate their society after surviving a plane crash and descending to murderous savagery. Fat, bespectacled Piggy is sacrificed; handsome, morally upstanding Ralph is victimised; and dangerous, bloodthirsty Jack is lionised, as the boys become 'the Beast' they fear. When the adults finally arrive, childish tears on the beach hint less at relief than fear for the future.

NB

Buy this book at the Guardian bookshop

• Go to 1000 novels everyone must read: Science Fiction & Fantasy (part two)

• Go to 1000 novels everyone must read: Science Fiction & Fantasy (part three)

Movie Title Screens - Sci-Fi & Creature Features of the Mid-20th Century (the 1950s): Title screens are the initial titles, usually projected at the beginning of a film, and following the logos of the film studio. They are often an ignored aspect of films, although they reflect the time period or era of the film, the mood or design of the film, and much more.Science fiction films took off in the early 50s during what has been dubbed 'the Golden Age of Science Fiction Films,' pioneered by two 1950 films: Rocketship X-M (1950) and Destination Moon (1950). Many of these films were exploitative, second-rate sci-fi flicks or B-movies with corny dialogue, poor screenplays, bad acting, and amateurish production values.

Teenagers From Outer Space (1959) Download Torrent 2017

Many other sci-fi films of the 1950s portrayed the human race as victimized and at the mercy of mysterious, hostile, and unfriendly forces, during the Cold War period of politics - with suspicion, anxiety, and paranoia of anything 'other' - or 'un-American.' These moods were reflected allegorically in sci-fi and horror films of the era. Threats and evils surrounded us (alien forces were often a metaphor for Communism), and there were imminent dangers of aliens taking over our minds and territory. UFO sightings and reports of flying saucers or strange visitors from outer space found their way into Hollywood features as allegories of the Cold War.

With the threat of destructive rockets and the Atom Bomb looming in people's minds after World War II, mutant creature/monster films featured beasts that were released or atomically created from nuclear experiments or A-bomb accidents. The aberrant, mysterious and alien monsters or life forms that terrorized Earth were the direct result of man's interference with nature. These profitable, low-budget horror/sci-fi/thriller hybrids were perfect for non-discriminating teenagers who attended drive-ins - caring little for character development, plot integrity or production values. Examples of these low-budget 50s films (many of which bordered the horror genre as well as adventure, fantasy, thriller and sci-fi) included The Thing from Another World (1951), It Came from Outer Space (1953), The War of the Worlds (1953), Them! (1954), Tarantula (1955), Forbidden Planet (1956), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and Attack of the 50-Ft. Woman (1958).

Teenagers From Outer Space (1959) Download Torrent Download

Other pages with title screens include All-Time Top Summer Blockbusters, Greatest Film Franchises (Box-Office), Highest-Grossing Films by Genre, Great War Films,Greatest Guy Movies of All-Time, and the Pixar-Disney Animations.